A Black River Story

An article by Alan Parfitt.

Gwent Angling Society has the good fortune to manage the fishing on about 3 miles of the upper river Sirhowy and a small section of its members have become regular and enthusiastic visitors to this wonderful but almost hidden fishery.

The story of the Sirhowy valley and its river is one with close parallels all across the South Wales minefield but since it contains our fishery it is the Sirhowy valley we shall focus on.

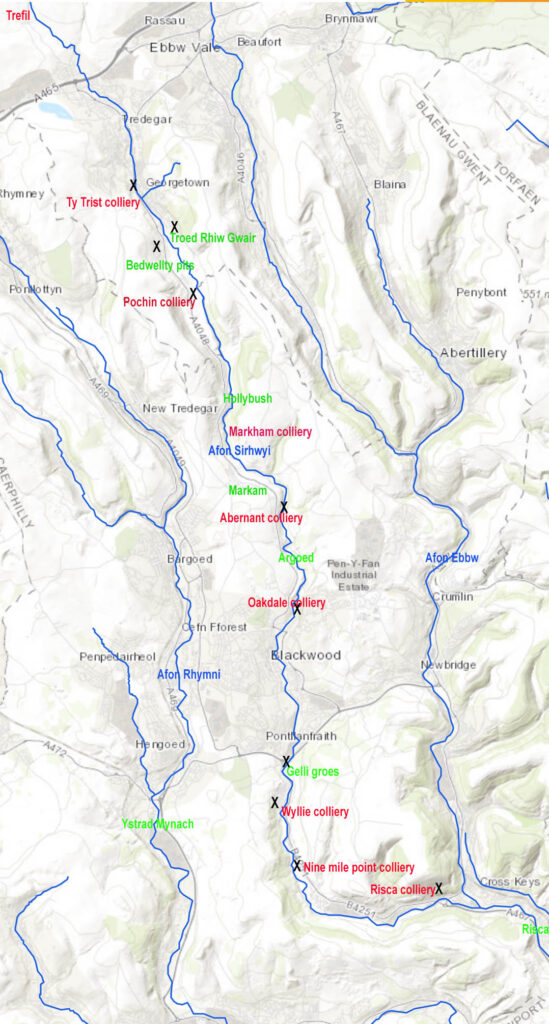

I was born less than half a mile from the Sirhowy or correctly Afon Sirhwyi in Tredegar. My dad’s parents were raised on one side of the river at Troed rhiw gwair while my other grandparents and mother lived opposite them in Bedwellty pits.

They were both mining families. I lived for 30 years in the Sirhowy valley and still live only 2 miles away so I can confidently claim to be a Sirhowy man through and through.

They were both mining families. I lived for 30 years in the Sirhowy valley and still live only 2 miles away so I can confidently claim to be a Sirhowy man through and through.

The source of the river is Nant Trefil on Mynydd Llangyndr just north of the old quarrying village of Trefil which at 1342 ft. claims to be the highest village in Wales. The river rushes down through one of the least known and most rural of the South Wales industrial valleys and has few major towns apart from Tredegar and Blackwood. Today, there is little evidence of the valley’s industrial past and the valley has largely returned to its natural best. This process of recovery has been a long and difficult struggle. The following brief account to tells the story of the river’s gradual rebirth in relation to its fishing together with some historical notes and personal anecdotes in the hope it will enhance the experience of a day by this lovely river and to appreciate how lucky we are to able to enjoy its piscatorial pleasures.

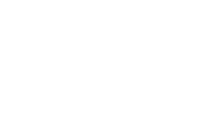

Although it is not ranked among the more famous Welsh mining valleys the Sirhowy has played an important role in local and even British history. The Sirhowy valley was heavily involved in the Chartist movement of the 1840s when working men marched down to Newport seeking equality and the right to vote. Tredegar was the home and benefactor of a giant of 20th. Century British politics, Aneurin Bevan, the famous labour politician, the architect and main driving force for the introduction of the British National Health scheme. One of the world’s earliest railways opened in 1805 travelled down the valley linking Tredegar to Newport to carry iron and coal.

The valley is also steeped in Welsh tradition. Just as you enter the peaceful village of Hollybush, travelling up from the Blackwood on the right-hand side is a signpost pointing the “Ancient Druid” cottages. Here there was once a pub of that name managed by an Evan James. His son James was born there. In later life, they moved to Ponypridd and here they co-wrote the Welsh national anthem though they were true Sirhowy valley men.

Further down the valley near Pontllanfraith is the tiny hamlet of Gelli Groes with its watermill , the last commercial watermill in Monmouthshire. In the 19 th. century the then miller, Aneurin Jones, ran eisteddfodau here and taught the young William Thomas “Islwyn” who became one of the most important Welsh language poets of the century and sometimes described as the “Sweet singer of Sirhowy”. Aneurin eventually emigrated to America and became superintendent of the parks and gardens of New York and Brooklyn. The mill was later run by the Moore family. Artie Moore, was an enthusiastic early radio ham and is said he suspended a copper wire across the river Sirhowy to act as an aerial. In 1912 he was the only person to pick up an SOS from the sinking Titanic. He rushed to the local police but was not believed as it was thought radio signals could not travel such a great distance. Two days later the reality came through. Marconi was so impressed by Artie that he gave him a job in the Marconi Company where he continued to develop many new innovations.

I was raised in the Blackwood area in the 1950s and 1960s about 10 miles down the valley from Tredegar. This was because, as will prove highly relevant later, miners and their families moved down the valley to the new coalmines at Oakdale and the Wyllie as the older collieries at the heads of the valleys became uneconomical and gradually closed. At this time there were a number of collieries in full production along the whole length of the valley. The river itself was simply called by everyone the “Black river” a term still recognised today by us older local folk. In that era much of the industrial and domestic demand was for lump coal and so the collieries had washing plants to remove the debris which was then discarded into the river as a black soup. Such was the quantity of “Duff” being carried by all the South Wales rivers that one company started dredging enough of it from the rivers Ebbw and Sirhowy to sell to power stations. As children, we were always warned to stay away from the Black River. It was said it would poison us, was infested with water rats (they were actually mostly Water Voles) and we might drown as no one knew how deep the pools were since no one had ever seen the river’s bottom. The exception was the annual miner’s holiday when all washing would stop for two weeks. Even then, though the water itself ran fairly clear with the coal dust still coating everything it did not really enhance its appearance by much. It was enough though for us to dream of what the river might be like if it ever became clean. It was a dream we thought at that time would never come true in our lifetimes.

Despite all the coal dust together with constant chronic sewage leakage into the river some fish still survived. I taught myself to fly fish on the neighbouring River Rhymni which like the Sirhowy was “bible black” but full of Trout and Eels. It was the only private fishing I have ever had as I was friendly with a farmer John Morris (John the Dyffryn) of Dyffryn farm, now sadly the site of the Dyffryn industrial estate and Ystrad Mynach hospital. He would only allow me to fish it and I soon learned the best way to catch Trout was with a dry fly. You could never see a fish but they must have hovered just an inch or so beneath the surface where I can only assume they could see the flies against the skylight. There were no “Hatches” just various insects blown onto and stranded on the water’s surface. You could certainly not see more half an inch into the black waters.

The vicissitudes of life ensured that there were many colourful characters in the valleys at the time. I fondly remember one old miner who often turned up in the evening to lean over an old stone bridge and watch me fish and have a chat. On almost every occasion that he appeared, I would have to endure the same advice. His favourite story was how he claimed to have cleaned out all the rats in Penallta colliery but he invariably parted with the same advice. “Always wear your trousers back-to-front boy” which he then expanded by stating “It will keep you out of trouble that way”.

The industrial rivers, fortunately, have small feeder streams and these remained clear and full of small trout throughout the industrial era. These I am sure had an important role in the recolonisation of the polluted rivers throughout South Wales after industrialisation and of course were a true local genetic stock. I remember once in a spell of hot weather and low river flow spotting about 30 trout, some up to about 2lbs, lying in shallow clean water where a small stream joined the Rhymni. They were there I am can only assume to get into the extra oxygenated stream water away from the sewage-contaminated river. You could eat Trout from the Rhymni at the time if you were desperate but very few did as they were reputed to have an unpleasant oily taint and some even thought them to be unsafe.

There were no Eels in the Sirhowy. The river joins the river Ebbw at Crosskeys and from here downstream it was totally devoid of life. A veritable cocktail of chemical waste from the Ebbw Vale steelworks mines and probably other sources meant the Ebbw was locally infamous for its ability to change colour several times each day depending on what was being washed into it. No Elver could ever survive to swim the 8 or so miles of the lower Ebbw to reach its confluence with the Sirhowy.

Amazingly, a pair of Kingfisher nested on the banks of the Ebbw at Risca. In the 1970s. The river was dead but they hunted the nearby canal which was full of fish.

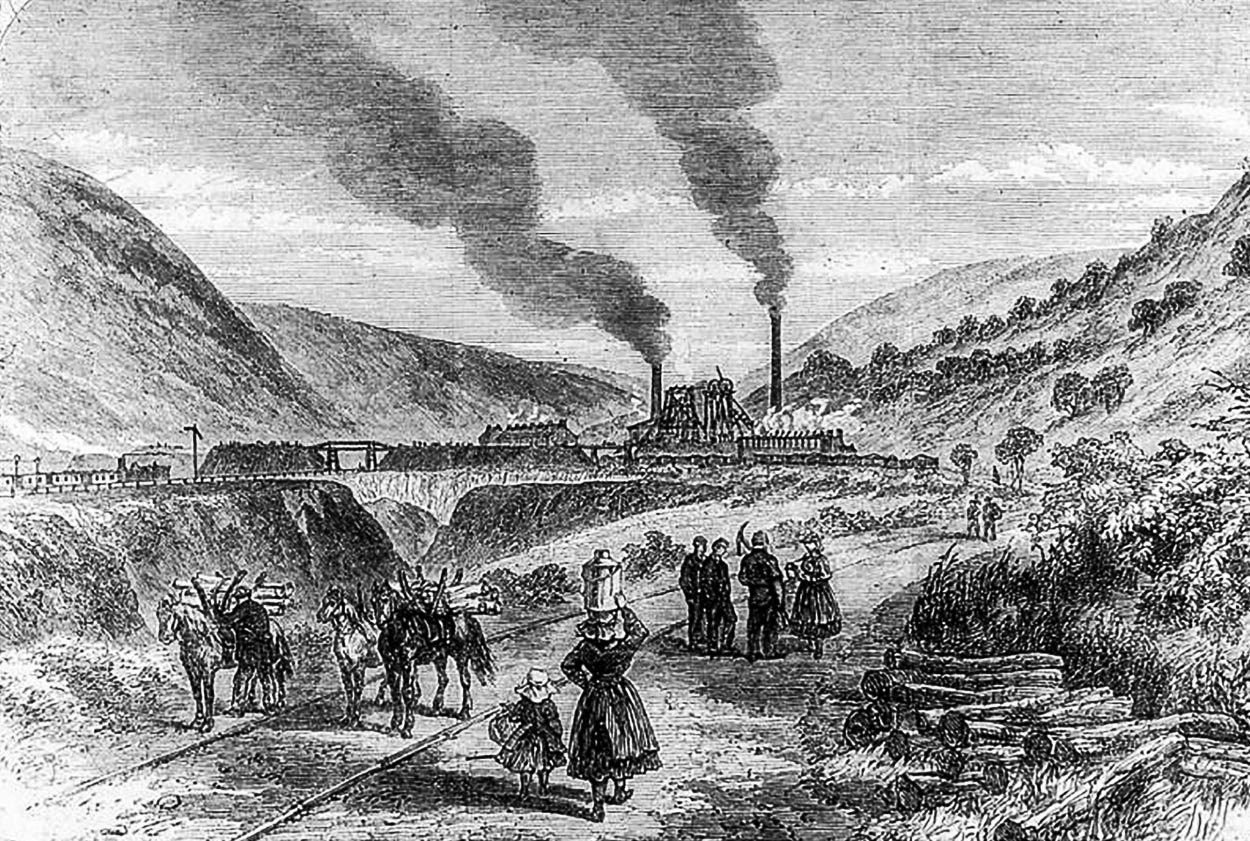

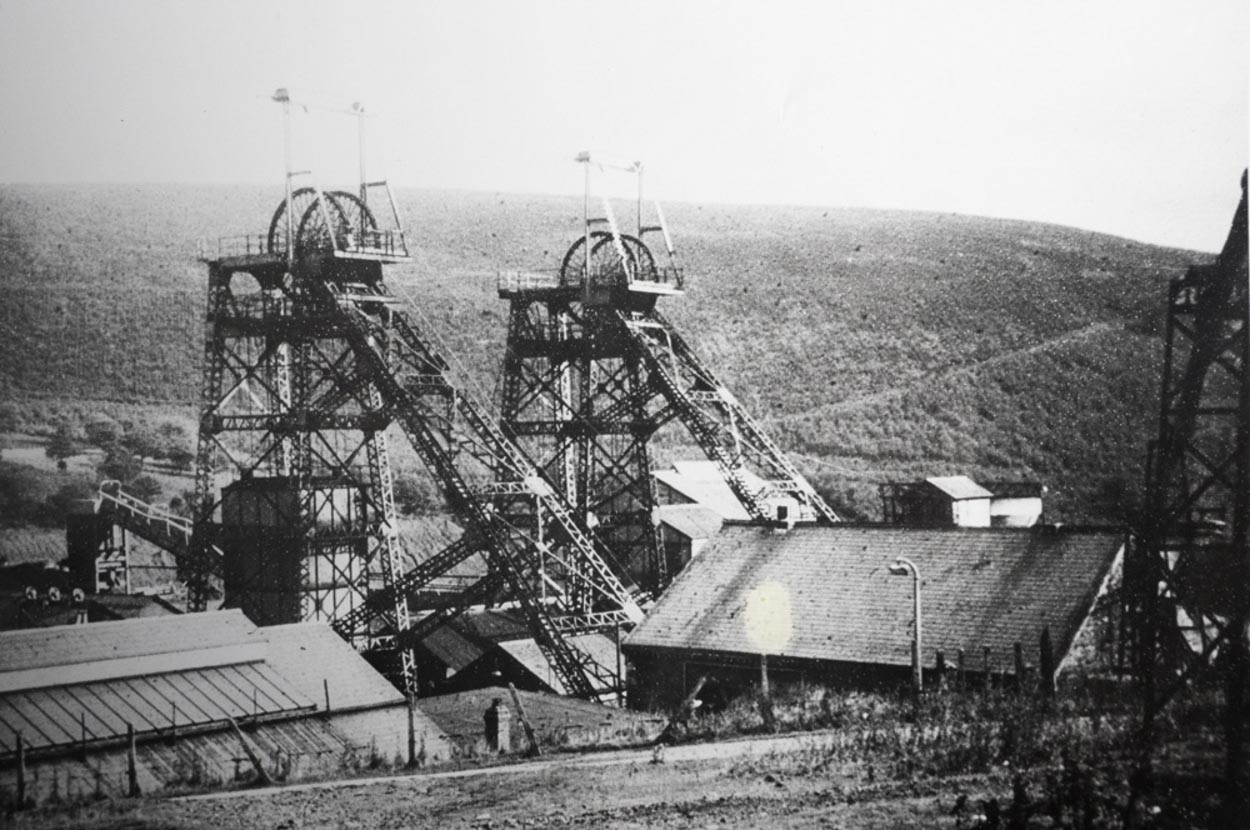

The big breakthrough came when Ty Trist colliery in Tredegar closed in 1959 after 125years of production. As the uppermost remaining pit in the valley, the river now ran clear of coal dust downstream for a few miles as far as Pochin colliery.

The big breakthrough came when Ty Trist colliery in Tredegar closed in 1959 after 125years of production. As the uppermost remaining pit in the valley, the river now ran clear of coal dust downstream for a few miles as far as Pochin colliery.

The trout soon appeared in numbers and I was fishing it with success almost as soon as the pit closed.. I always remember a huge trout that lived in a long pool below Troedrhiwgwair. The bed of the river was then still quite black with residual coal dust and the fish were correspondingly dark. This particular specimen, which may well have been several pounds in weight, used to hide beneath an old sunken Oak trunk and could sometimes be spotted as he intermittently displayed a flash of the white inside of his mouth as he breathed. I never did hook him but I suppose his wisdom of all things suspicious had ensured his ability to grow to such a size.

Upstream worming was the method I used exclusively to catch my Trout. I think I am justified in boasting that I became quite an expert at this technique. It is a vastly underrated method of fishing and in its purest form requires as much skill if not more than fishing the fly. In times of high water, it was quite straightforward and easy to get a few fish with a worm but when the river dropped to low clearer water flows then the skill needed rocketed to very high levels indeed. All you needed was any old light rod with a fixed spool reel and about 4lb. monofilament, a hook and worm. You also needed a small pocket to carry a small packet of spare hooks and a tobacco tin with a dozen worms. No waders then just wellington boots. You had to wear “Wellies” because all our mothers always insisted we had to keep our feet dry to avoid rheumatic fever.

The tactic was to creep up to the tail of a pool and if necessary wait for any wary fish to settle down. It was quite easy to tell from the behaviour of trout if it was aware of you. Alarmed Trout do not always shoot off into the deep water even though they were aware of your presence and though it is difficult to explain you could always sense when they knew you were there and ready to escape. Such fish would never take the bait as they were too busy watching you and waiting to flee. I usually used the theory that if you could see them they could see you. You cast upstream into the neck of a pool and allowed the worm to drift back as naturally as possible. Searching all likely places. You could not cast more than 5 or 6 yards so stealth and keeping a very low profile was crucial. I do not think many modern fly fisherman really comprehend what a stealthy approach is. Attaching split shot or weight of any kind destroyed the worm’s movement so your only casting weight was the worm itself. All the fishing books sang the praises of the Lob or dew worm. This taught me at a young age to have a healthy scepticism for much that is written and perpetuated in angling books. It is a conviction I still have to this day. The best way to learn is from your personal experience and experimentation. If you want to know something ask a person who has done it not written about it. Trout may well like Lobworms but in practical terms I found them to be waste of time falling apart within a cast or so. Easily the best were Brandling worms as they were tough yet just about big enough to cast. The real enemy of an upstream wormer is rain because the rod would get wet and the monofilament would then stick to the rod blank making casting such a lightweight impossible.

The early morning was the best time to fish and by about the early ’60s, I had my fishing routine sorted. During the school summer holidays, I would get up about 3.00 am and cycle up the valley to Pochin colliery. It still washed coal at the time so that was where the clear water upstream started. My bike would be hidden in the ferns and I would gradually work my way up to Brompton bridge (now called Peacehaven) at the bottom end of Tredegar. By early morning I was finished and would walk back downstream to my bike via. Bedwellty pits village. My Nan’s youngest sister lived there so I would be welcomed with some toast and tea before heading home. Those were good days.

In 1964 Pochin Colliery closed and the river soon ran clear down to Markam colliery and it is this stretch which now constitutes the major portion of the GAS Sirhowy waters.

A few years later all coal mined at Markam was brought to the surface at nearby Oakdale colliery so even more of the river was able to recover. Unfortunately, Oakdale colliery continued to work coal for several years (closing in 1986) and through this period it still intermittently washed coal, though the silt load was now much less than in previous years so even the lower river showed improvement.

The winter of 1963 it is said was the hardest of the 20th. Century. It was great because we were given so much time off from school. By spring I was back on the river and still had the river more or less to myself as the word about the quality of fishing had still yet to fully circulate. That spring I caught my biggest fish just below Markam at 3.5 lbs. It was still lean after the long winter and I believe would have topped 4lb. later in the year. All the South Wales rivers are capable of producing large fish as the water unlike mid-Wales is slightly alkaline and promotes excellent growth rates.

Sadly, the mine-related problems did not cease with the end of coal washing. The river had long been perceived as a convenient way to get rid of about any waste which could be washed down the river and it took many years of vigilance, prosecutions and enlightenment before the rivers become biologically stable. Between Markam and Oakdale collieries was the old Llanover mine. The South Wales coalfield was renowned for being very wet and enormous quantities of water had to be pumped from the mines daily. At Llanover huge pumps were installed which kept both Oakdale and Markam workable. This water could raise the river level by a few inches. When the mines eventually closed and the pumps stopped a new unexpected problem appeared to threaten the health of the rivers across the whole south Wales minefield. This new threat came in the form of iron oxide (rust) contaminated water seeping from the old mine workings. The coal seems are full of Iron deposits, which in the absence of continual pumping oxidises in the drowned workings.

Eventually, orange stained water drains into the rivers. Especially in springtime, the whole bed of some stretches the river become coated an in orange/rust colour. Although not directly poisonous the river becomes uninhabitable to invertebrates as the orange deposit smothers the whole river bed. I remember once on the lower river Neath seeing a large sea trout almost the colour of gold, the fish having been contaminated by “rust water” pouring into the river from the contaminated canal above it. Fortunately, on several rivers, the mine water is now diverted into special reed beds, which thankfully are able to remove the pollution. The Sirhowy, though, still has this problem in the Blackwood area from the old Oakdale colliery and every spring runs orange for a few miles before it eventually disperses.

I began my teaching career at Pontymister school in Risca in 1968 and was soon roped in by a colleague, Peter Winmill, (“Pete the Plank” to his pupils while I was “Johnny Compost”) to join a “mad” group of misguided but dedicated individuals who had formed the Risca fly fishing club. Peter was another valley character and was always making up tall tales, especially about his days in the Navy for his pupils. He always told them he could flick a cigarette out of a boy’s mouth with his fly rod at about 20yds.

Under the visionary Dr Michael Wade, the club started acquiring fishing rights on the Sirhowy and Ebbw rivers. The Ebbw was a dead river at the time but Dr Wade could see the future where others could not. What makes it even more remarkable is the Wade family owned a wonderful stretch of the River Usk (and still do) so the crusade was not through self-interest but for the whole valley community. You can read more about this remarkable man in a separate article on this website. We would initially stock the lower Sirhowy in the 1970s even though it still carried coal dust. The fish never survived for long in the first stockings as a result of frequent pollution episodes followed by legal proceedings against the polluters. Gradually the period between fish kills lengthened towards the stability we have today. Fishing clubs also formed further up the valley and the GAS Sirhowy water is that of the old Markam Angling Club. In the 1970’s the three clubs on the lower river, Risca, Ynysddu and Cwmfelinfach, together with Blackwood Angling club amalgamated to form the present-day Islwyn and District Angling Club. Today the quality of trout fishing on the lower Ebbw is of the highest quality together with modest runs of both Sea Trout and Salmon.

So there you have it. We have made a brief journey down the valley through both time and an environment recovery. Let us hope the future remains bright.

Note

Day tickets and membership are available through “Islwyn and district anglers” on the lower Sirhowy and Ebbw rivers at Green’s fishing tackle shop in Pontllanfraith. Day tickets are available online through their website.

WHY NOT JOIN US?

The Gwent Angling Society is a progressive, conservation-minded club offering fishing on six beats on the River Usk, two on the River Wye, the Sirhowy river and Afon Llynfi (Powys), and the wonderful Talybont Reservoir. Our waters can be viewed here. If you are interested in joining us or have any queries, simply contact our Membership Secretary.